There’s something so primal about caves.

Before primitive huts of grass and sticks forever changed the landscape; before endless rows of tract homes lined suburban streets; before glass-clad high-rise apartments pierced the indigo sky, our ancestors sought shelter in naturally-occurring structures: caves.

Caves were our first “homes”. To this day, we humans continue to be fascinated by caves. And it’s completely natural; it’s in our DNA. Caves provide us with shelter from the elements. Caves provide protection from our enemies. We humans have evolved to feel safe in caves.

—–

Fossils were observed in Sterkfontein Caves, a limestone cave complex on the high plains of South Africa, as early as the 1890s. The fossils that the quarrymen came across as they mined the limestone for sale were no more than a curious by-product of their primary plunder. Instead of ending up in a museum or at a university where they rightfully belonged and could have played an important role in the advancement of science and understating our origins, they were instead sold to local tourists as interesting oddities.

In 1924, these quarrymen discovered a fossilized skull at Sterkfontein which became known as the Taung Baby. By blind luck and happenstance, it eventually found its way to a South African named Dr. Robert Broom, who took pains to describe it and share it with the scientific community. But Broom’s efforts were met with much ridicule because of his lack of training as a paleontologist, his lack of affiliation with a respected research institution, and the audacity of what he was proposing: that the Taung Baby represented not a proto-chimpanzee, but a proto-human.

Tickets to enter Sterkfontein Caves.

It wasn’t until the 1930s that formal excavations at Sterkfontein Caves started by Broom and Prof. Raymond Dart turned up additional fossils and confirmed Broom’s assertion of the presence of a proto-human species, Australopithecus africanus. The series of finds rocked the fields of paleo-archaeology. The fossils from Sterkfontein were identified as a missing link between man and the apes, and the area became known as “The Cradle of Mankind”.

—–

Sterkfontein was relatively close to where we lived northwest of Johannesburg, so it was an easy place to visit. We went there on numerous occasions over several years.

The entry fee to the caves was 60 cents per person. Tours ran every half hour, and it didn’t seem like a very popular place: we almost always got a “private tour”. The sign on the heavy iron gate protecting the entrance to the cave read “No Entry / Geen Toegang / Ikona Ngena”, a warning in the three predominant languages of South Africa. As the gate was unlocked and we crouched to descend down steep stairs into the belly of the cave, the light quickly faded, until we were surrounded by cool, dark rock, with a bright light overhead coming from the single slit of sky still visible through the crack in the earth which defines the beginning of the Sterkfontein cave system. Before long, stalactites could be seen hanging from the ceiling, stretching almost all the way down to the floor of the cave. It was like entering a primeval world.

The entrance to Sterkfontein Caves.

Our tour guide pointed out fossils still sitting in place in the limestone matrix, as well as holes in the limestone where some of the world’s most famous hominid fossils had already been removed. It was incredible to be so close to such an important part of ancient human history. But beyond the paleo-anthropological significance of the cave, the fragile ecosystem was also quite fascinating.

Dropping down in to Sterkfontein Caves.

Inside the cave is an underground lake, it’s clear, cool waters stretching for more than 10 miles. According to notes written in my journal in July 1977 when I was 14 years old, the air and water temperatures in the cave and lake had equalized at a brisk 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

For some unknown reason, the water level of the cave was rising rapidly; between 1976 and 1977, it had risen by at least 8 feet. Indigenous to this lake is a form of albino blind shrimp, about half an inch long. During my 1976 visit to the caves, I saw many shrimp in the lake. Returning there in 1977, I only saw two shrimp. At the time it was speculated that the rising water level was negatively affecting the habitat of the shrimp.

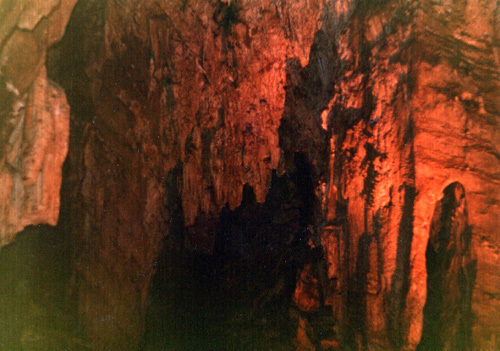

Stalactites deep in Sterkfontein Caves.

Other than the shrimp and the few visiting humans, the only other life I ever saw in all of my visits to the caves was two pigeons and a single bat. The cave seemed to be habitat more suitable for dead things than it was for living things.

—–

I had always been captivated by history, and the older the better: thus, Greece was more interesting than Rome, but Neanderthals were more interesting than Greece, and Homo Erectus was more interesting than Neanderthals. If older equaled more interesting, you couldn’t get much better than witnessing first-hand the birthplace of the Sterkfontein fossils.

In 1981, I enrolled at Pasadena City College. Because I enrolled late, the selection of available classes was limited: for my selected major, Drafting, all classes were already full. I stood at the registration table, knowing that I really needed to go to college, yet not having any classes in my major available to take. So I quickly ran through the list of available classes. I just had to take something.

The few classes still open were listed in alphabetical order, so it didn’t take long before I came across several Anthropology classes which were still available.

“Anthropology has always been very interesting to me,” I thought, “so I guess I’ll major in that.”

And the rest is history.

I worked as a tutor in the Anthropology Department, helping students to understand the intricacies of physical anthropology, cultural anthropology, and archaeology, while holding office hours in the lab surrounded by plaster casts of all the famous fossils of paleo-anthropology, including those found at Sterkfontein Caves. Later, I transferred to Cal Poly as an Anthropology/Geography major, worked in the Anthropology Lab there, and participated in archeological field digs in southern California. But wherever I went, when Broom’s finds at Sterkfontein Caves came up in lectures or discussions—which they did frequently—I marveled at my incredible stroke of luck having been transported halfway around the planet to live in a place just down the road from one of the most important paleo-anthropological sites in the world.

—–

One of my most vivid memories of my adolescence in South Africa took place deep in Sterkfontein Caves. We arrived a few minutes before the next scheduled tour, and bought our tickets. The man behind the counter tore a rough notch out of the corner of each ticket, handed them back to us, and then watched the clock. We were the only ones there for the next tour, and if nobody else showed up in another minute or two, we would have a private tour! Then, at the very last minute, a large group of black people showed up to join our group.

You must remember that this was apartheid-era South Africa. Blacks and whites lived in separate communities, rode separate trains, used separate bathrooms and drinking fountains, and even swam at separate beaches. In this carefully orchestrated environment of discriminatory separation, I had encountered very few situations like this where black people and white people interacted.

I may be anti-social, but I’m not racist. I was upset that my hopes for a private tour had been dashed, but I was also very curious how a tour featuring a mixture of the two races would pan out, as I had never experienced anything like it before in South Africa under apartheid.

They appeared to be a church group of about 12 to 15 people, all approximately in their mid-twenties, about two-thirds of them male. Everything seemed perfectly average until we arrived at the underground lake. They began to chant what I thought sounded like a native religious song. As they approached the edge of the lake, they each pulled empty bottles out of their jackets and started to fill them with the cool, pure cave water.

Was there a religious significance? Did they think the cave water had some sort of magical healing powers? As I pondered this, one of the men fell to the ground with a large thud and started convulsing violently. I imagined that he was having a deeply religious experience, his body suddenly possessed by angelic and/or demonic spirits, and that his possession might have something to do with the mystical powers of the water being taken from the underground lake.

His friends gathered around him, lifted him off the ground, and tried to comfort him as they carried him back out of the underground cavern. The cave quickly returned to a peaceful, calm silence, and I stood there wondering what in the world I had just witnessed.

Years later, I realized that this unfortunate gentleman had not been possessed by a god or a devil, but had simply experienced an epileptic seizure.

—–

This story is excerpted from my book Down to Africa [ Paperback | Kindle | iPad ].